The story of the refuseniks begins with the emergence of the Soviet Union in 1922. Read about the events that lead up to this dramatic time in our Historical Overview below. Play with the Interactive Timeline and discover photos and videos along the way.

Historical Overview

A Very Brief History of the Jews of the Soviet Union, 1922-1991

The Beginning

After a series of bloody revolutions and wars beginning in 1917, the Soviet Union (USSR) emerged in 1922 as a communist country. For the approximately 3 million Jews living there during the early years of the regime, there was room for cautious optimism. Antisemitism was not tolerated on an official level, many Jews were active in the Communist leadership, and economic hardship seemed a thing of the past.

Quite quickly, however, optimism ebbed. As authorities consolidated power, they worked toward the elimination of organized religion, with the official goal of establishing “state atheism”. Members of all religions – Russian Orthodox, Catholics, Baptists, Protestants, Jews – were targeted. Harassment, property confiscation, imprisonment, and the murder of religious leaders were all used to create an unforgiving environment in which organized religion ground to a halt. Parallel to this, the government mobilized ethnic groups for Communist purposes: ethnic groups could use their language, could write and read their own literature, could join and watch their own acting troupes, as long as the content was Communist, as long as it did not support a separate national sentiment or identity.

Judaism suffered. Autonomous Jewish institutions disappeared. Communal Jewish leadership ceased to be. Hebrew language education and religious teachings were forbidden. Amidst the strong anti-religious stigma by the State and the media, the propaganda that all ethnicities and religions were irrelevant in the making of a “new Soviet man,” and in the violence, the police state, and the famine that made up life in the USSR, Jewish identity slipped quietly away.

The Holocaust and Its Aftermath

In 1939, with the Soviet annexation of territories from Poland, the Baltic States, and Romania, the number of Jews increased to 5 million.

In 1941, the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union. In addition to standard military units, the Nazis brought mobile killing units (Einsatzgruppen) to eliminate the Jewish population. Jewish Soviets who had shed their Jewish identities were Jewish again, singled out for punishment by the Nazis and their collaborators. Although the USSR was eventually victorious, the country lost 30 million people, of them 2.5 million were Jews who were massacred by the Nazis.

Post-war, Jewish identity was revived by a paradoxical Soviet policy. On the one hand, from a governmental perspective, the Soviet Union was made up of “Soviets”, not separate ethnicities, and to allow the Jews to publicly mourn Jewish victims would deny that “fact.” That is to say, Nazi victims were referred to as “Soviet citizens” or “civilians” and suppressed any mention of the Jews. On the other hand, the government aggressively pursued antisemitic policies. Jews were dismissed from certain professions. Jewish cultural organizations were dismantled. Jews were targeted in continual smear campaigns by the media, in which the Soviet public learned that Jews were involved in a conspiracy to bring down international socialism. Yiddish artists and intellectuals were arrested and murdered. Key Jewish personalities were imprisoned and sent to labor camps. Told that they were not Jews, but forced to be Jewish, the Soviet Jewish population was increasingly alienated from the general population.

Jewish Revival

Beginning in 1953 with the death of Stalin, there was a quiet Jewish revival in the Soviet Union. It began with Jews connecting to other Jews in different neighborhoods and then cities, discussing Jewish topics, or listening to Israeli radio stations on shortwave radios. It continued with the underground production and dissemination of samizdat, uncensored texts, newsletters, and journals that explored Jewish beliefs, history, and identity. The government and the secret police continually pursued anti-Jewish policies and propaganda, although the intensity and coordination of the activities were uneven depending on the personalities in power and international affairs.

In 1965, an Israeli newspaper sent Elie Wiesel—then a young author—to report on the lives of the Jews in the Soviet Union. He was astonished by what he found, and his resulting book, The Jews of Silence, in turn, shocked the world. He described a country in which its Jewish citizens were cut off from the rest of the world, afraid to discuss Jewish subjects or Jewish people. Soviet Jews lacked fundamental knowledge of Jewish things: holidays, history, and language, and yet, these Jews celebrated Jewish holidays as best they could, with considerable risk. “Despite everything,” Weisel wrote, “they wish to remain Jews.”

The Refuseniks

The Six-Day War in 1967 initiated a new phase in Jewish consciousness in the Soviet Union. The Soviet government had supported Arab countries and had outfitted them with Soviet arms. The defeat of these countries by Israel, a fledgling country, was not only a shock to the Soviet government but a betrayal. While Soviet media pumped out anti-Zionist propaganda, declaring that all who supported the Zionist cause were enemies of the people, Soviet Jews began to feel not only pride in being Jewish but to acknowledge a common national fate.

Many Soviet Jews dreamed of moving to Israel, but making that dream a concrete reality was almost an impossibility. To emigrate from the USSR, one needed approval from the Soviet government. Most Jews who applied to leave were rejected. These rejections were generally given without explanation, although some applicants were told that they knew “state secrets” that could be divulged to the West. The applicants were then in a “state of refusal” and became known as “Refuseniks.” This period lasted months, usually years, and sometimes even decades.

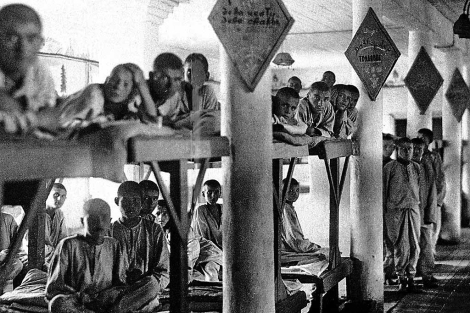

Perhaps the feeling of imprisonment would have engendered psychological damage on its own, but it was coupled with the harsh realities of being in a “state of refusal.” Having made the request to leave, the Refuseniks were treated as enemies of the state: they lost their jobs or were demoted, they lost their homes, and they were continually followed and bullied by the secret police. Many were arrested and imprisoned on imaginary or trumped-up charges (prisoners who were arrested for Jewish practice or pro-Zionist activities are called “Prisoners of Zion”).

Protest

The Refuseniks responded in two central ways. On the one hand, they continued to build their Jewish lives—covertly, of course—whether it meant teaching or learning Hebrew, celebrating the Jewish holidays in the forests where police surveillance was difficult, or congregating with other Jews to learn Jewish history and texts. They found meaning in Jewish expression whether their connection to Judaism was secular, traditional, or religious. On the other hand, the Refuseniks publicly challenged the government by writing and distributing letters of protest to the media and passing on details of the harassment and injustices to Western journalists and government officials. Their behaviors became more and more audacious, including a planned hijacking of an empty plane, to get attention.

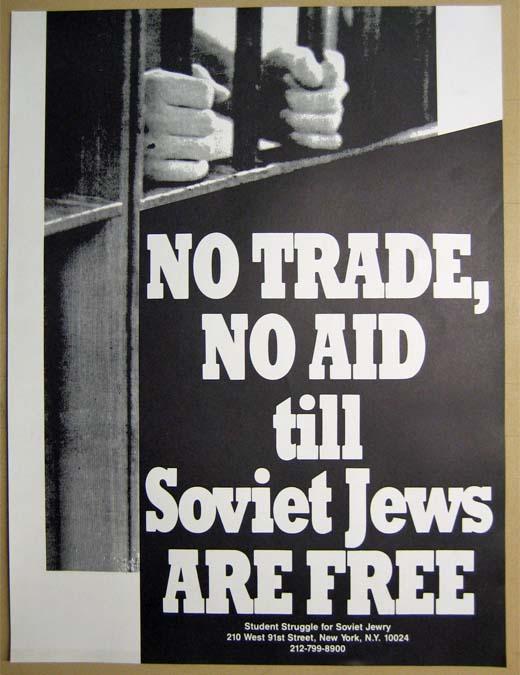

The courage of the Refuseniks fired up the passions of the Jews of the West. In the 1970s, memories of the Holocaust lay heavily on the Jewish community, and many Western Jews could still point to far-off relatives living behind the Iron Curtain, their ancestors having emigrated to the West from Eastern Europe.

Western Jews threw themselves into protesting the status of Soviet Jews: organizing marches and candle vigils, reaching out to their congressmen, and facilitating media coverage. They created organizations, raised money, and sent activists to the USSR to see conditions for themselves. They regularly communicated with Refuseniks by telephone and mail, to keep current with the situation and to offer help where they could. They pressured politicians into including human rights clauses and Jewish emigration into legislation that governed American-Soviet relations.

At some point, a cycle emerged: the spirited behaviors of the Refuseniks emboldened the Western Jewish activists, while knowledge of Western support heartened the Refuseniks. Risks increased on the side of the Refuseniks as arrests, bogus trials, and real imprisonments skyrocketed, and Western Jews amped up their campaigns, sharing the plight of the Soviet Jews with the world.

The Soviets responded in a confounding way. They allowed some Refuseniks to emigrate, jailed others, and kept the majority in limbo, in a state of refusal. As dismal as the situation was, the exit visas obtained by some Refuseniks demonstrated that pressure had an impact—there was hope.

The End/The Beginning Again

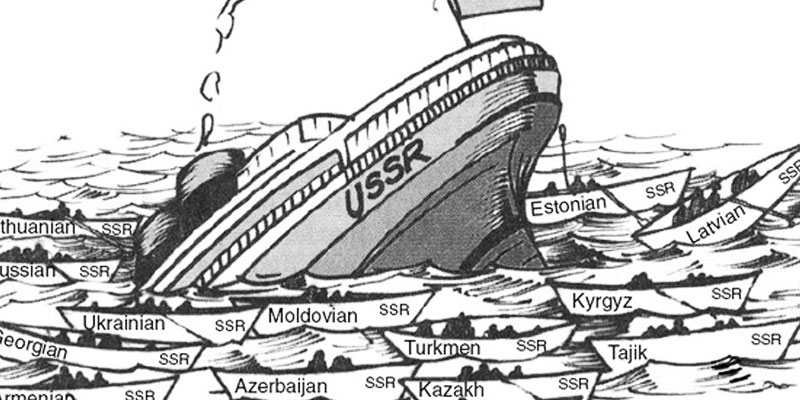

By the mid-1980s, the USSR was stagnant, its economy barely functioning, and its population bent under the weight of a police state. International support for the Refuseniks was at its height and Jewish emigration was at a low. Thousands of Refuseniks were waiting to receive exit visas; hundreds of Jews were imprisoned in gulags and jails in remote parts of the country for daring to demonstrate Jewish or Zionist behaviors.

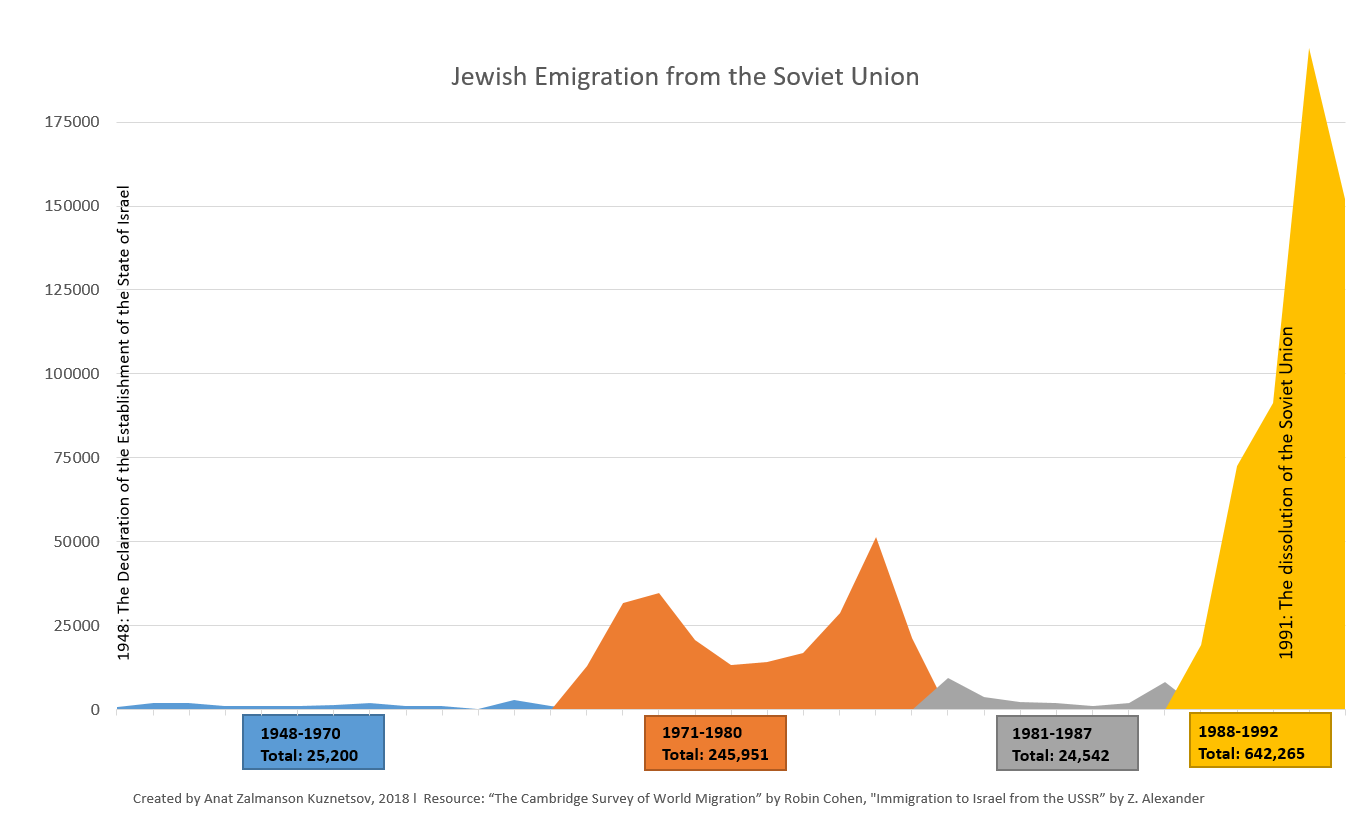

A change came in the form of Mikhail Gorbachev, a young politician who, over time, recognized that the situation was untenable. Slowly laws were passed allowing more freedom of speech, and more economic freedom. Activists were released from prison, including Prisoners of Zion. Beginning in early 1987, Refusenik cases were reviewed and exit visas issued. In 1986, only 904 Jews had been given these visas—by 1987, the number jumped to 8155.

In 1988, the Soviets permitted Israeli officials to reopen the Israeli embassy, which had been closed since the Six-Day War. Immediately, would-be emigrants formed long lines outside the embassy, desperate for exit visas from the USSR. In this environment, Jews began coming out of the woodwork, establishing Jewish organizations—research centers, libraries, cultural associations—in large Soviet cities.

But for many, this was too little, too late. The liberalization allowed Jews to recoup their identities as Jews and perhaps to build a full Jewish life, but at the same time, it meant that latent anti-Semitism, held in check to a certain extent by state policies, was now rampant. By late 1989, and until the total collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, emigration had become practically free. Close to half a million Jews left in the space of a two-year period (of these about 70% went to Israel), with another million Jews joining them in the decade after.

Interactive Timeline

Chronology of Major Events was prepared by Yuli Kosharovsky and Enid Wurtman, with the help of Pam Cohen and Jerry Goodman.

You can see their original work here: http://kosharovsky.com. The interactive timeline below was edited by the Refusenik Project team.

Soviet Revolution emancipates Russian Jews from Imperial Russia's anti-Jewish measures

Hebrew and Yiddish schools are closed by order of the government

1919-1929

Gulag administration is established

Over time, Zionist, religious, and other Jewish activists perish or suffer in the Gulag system.

1930Jews (“Yevrei”) and other national minorities are now identified as such on individual identification documents

1932The first large anti-Jewish purge takes place

Jews removed from positions of leadership.

1938World War II and the Holocaust

Death of 2.5 million Soviet Jews.

1939-1945

Israeli envoy and minister, Golda Meir visiting Moscow, dancing with the Jews on Rosh HaShana. The Jewish gathering was unprecedented in Stalin's Moscow, whose residents did not dare holding spontaneous demonstrations. The response was not long in coming; Most of the Jewish institutions in the USSR were closed, and it was made clear to the Jews that Israel would remain a distant dream for them. But the Jews decided otherwise. Golda's visits to the synagogue became a founding myth for them and were later commemorated on the banknote bearing her portrait.

1948

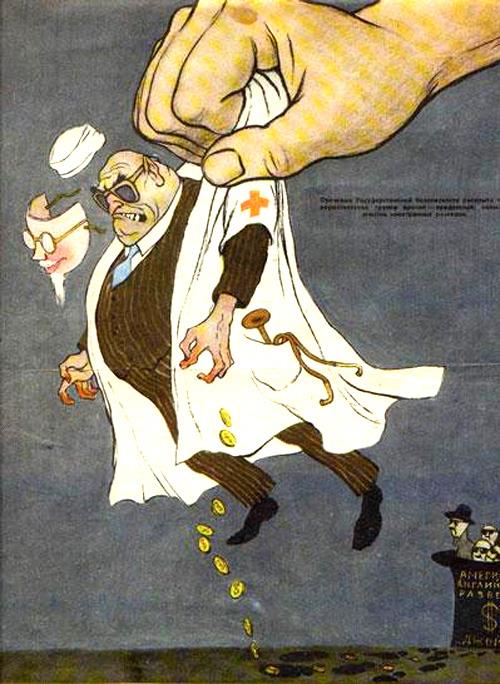

“Doctors Plot” campaign accuses Jewish doctors of planning to kill Stalin and other officials

Stalin dies on Purim and the trial of the doctors is cancelled.

1953Israel establish "Nativ"

The Government of Israel establishes a secret unit that will deal with the issue of the Jews of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, within the framework of the intelligence services of the State of Israel: "Nativ" (=Path)

1953The first U.S.A "Freedom For Soviet Jewry" activist group is formed In Cleveland, Ohio by a NASA scientist

It later becomes the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews. Over the next decade, many other advocacy groups are formed..

Read More…1963Mordechai Lapid, a Soviet Jewish leader, is imprisoned for organizing a gathering to welcome an Israeli singer

In response, thousands attend a National Eternal Light Vigil, the first public demonstration in Washington, DC.

Read More…1965Elie Wiesel’s book, The Jews of Silence, is published

It highlights his encounters with Soviet Jews and the silence of Western Jews in the face of their plight.

Read More…1966

Israel's victory in the Six-Day War is an inspiration for many Soviet Jews, who now feel that they can struggle against Soviet oppression

196718 Soviet Georgian Jewish families appeal to the United Nations for their right to leave the Soviet Union

Their appeal captures the attention of the Western media. In the USSR, a secret committee (VKK) is created by Jewish activists in the Soviet Union, to coordinate efforts.

Read More…1969Soviet Government organized television broadcast showcases elite "State Jews" condemning Zionism and emigration

16 activist-refuseniks attempt to "hijack" an empty plane ("Operation Wedding" / 1st Leningrad Trial) in an act of desperation to reach Israel

The arrest and trial galvanized major international support. Pressure from the West led the USSR to commute death sentences and allow hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews to emigrate.

1970First World Conference on Soviet Jewry is held in Brussels with 800 delegates including prominent Israeli leaders David Ben-Gurion and Menachem Begin

1971Jewish activists in the USSR issue The White Book of Exodus containing numerous personal letters and appeals; it is published in the West

1971The USSR introduces an emigration tax aimed at educated would-be emigrants, particularly Jews

It is considered to be a “ransom” tax meant to deter Jews seeking to leave for Israel. Word of the education tax stirs protests in the West.

Read More…1972Senator Henry Jackson proposes legislation linking access to trade benefits for “non-market” (i.e. communist) nations to liberalize their emigration practices

This becomes the Jackson-Vanik Ammendment in 1975, the most effective legal tool in the fight for Soviet Jewry.

Read More…1972The “Final Helsinki Act” is signed by 35 nations including the USSR at an international summit

The Act, among other things, focused on human rights. The document becomes a global instrument used to improve human rights in the USSR, especially Jewish emigration.

Read More…1975Soviet television premieres an hour long anti-Zionist documentary "Traders of Souls",; which specifies the names and addresses of prominent refuseniks

This serves as an invitation for harassment and violence.

1977Human rights activists and refuseniks, including Anatoly (Natan) Sharansky, are arrested on trumped up charges of treason and spying

This is seen by Washington as a Soviet challenge to the humanitarian provisions of the Helsinki Final Act and an obstacle to US-USSR détente.

1977140 dissidents, Refuseniks, and Prisoners of Zion are pardoned and released

This period can be considered the real beginning of perestroika in the field of human rights.

1987

A record 250,000 people participate in the largest rally ever organized in the U.S. on behalf of a Jewish cause

The event marks the peak of the Soviet Jewry advocacy campaign in the US.

1987The Soviet government establishes numerous Jewish cultural institutions

1988The Israeli government organizes direct flights to Israel and establishes a consulate in Moscow

A wave of Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union begins. 1988The Soviet government approves a human rights declaration which includes the Right to Leave and the Principle of Family Reunification1989